Among Connecticut’s roughly 500,000 K-12 students, 39,000 adolescents (ages 12-17) were reported to have at least one major depressive episode in the last year, and more than half experienced severe episodes. Only 24,000 received treatment.

The statistics on children’s mental health are sobering. Yet despite these grim numbers, Connecticut ranks eighth in the U.S. for youth mental health—which means in most states, the problems are even worse and the solutions fewer.

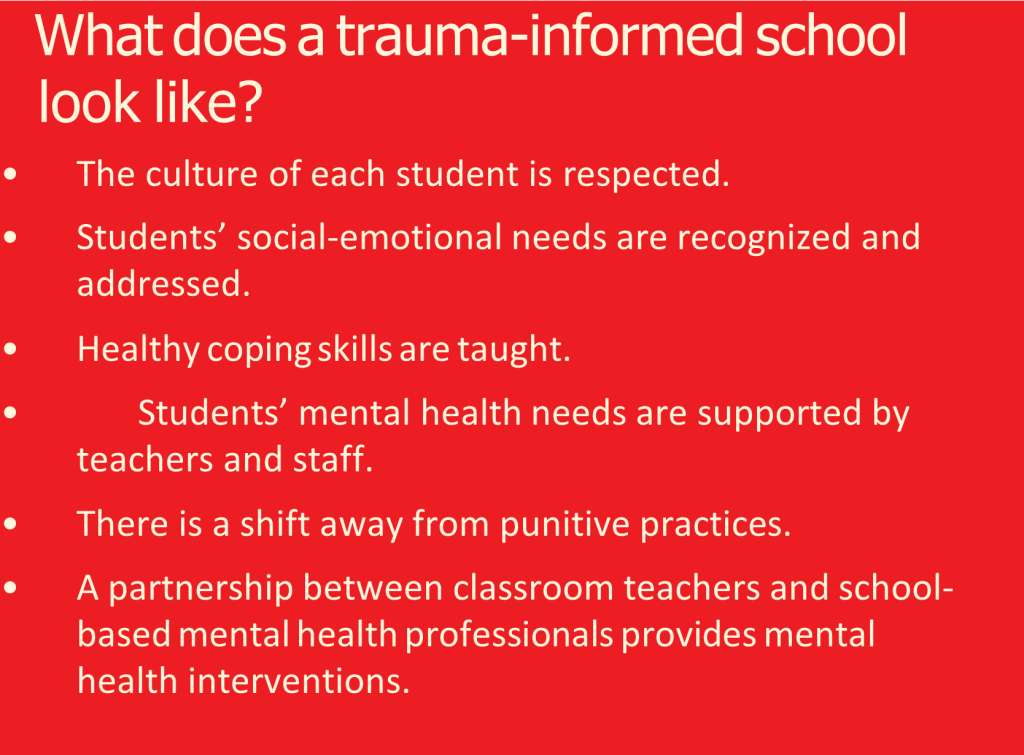

So, how do you create a classroom environment that supports students who may be struggling? How do you even know who those students are? Can educators be a significant part of the answer to a complicated and wide-ranging problem?

This week is National School Psychology Week, a week dedicated to highlighting the critical work school psychologists do to help students thrive.

Granby school psychologists Kim Bressem and Heidi MacDonald have made a study of these issues, and together, they’ve conducted training to help their colleagues in the classroom understand them too.

“Since COVID, kids are different,” says MacDonald, who works with fourth- and fifth-graders. “We’re different. Before COVID, one in ten school-aged children had a mental health disorder. Today, it’s one in six. At the high school level, it’s one in three. And research tells us our girls have fared worse. On the whole, girls tend to internalize. Being pulled out of their social circles during COVID was particularly hard for them.”

While the number of children presenting with mental health issues has nearly doubled since COVID, MacDonald notes, “They didn’t double me.”

In fact, for every 548 schoolchildren in Connecticut, there is only one school psychologist, and the ratios of students to school counselors and social workers are similarly problematic, even as state legislation has sought to remedy the imbalance.

The biggest protective factor against mental illness is social connection, says MacDonald, but opportunities for connection have decreased in ways that cut across socioeconomic lines. In cities and towns with tight budgets, the spaces that provide critical social connection—community centers and after-school clubs—are often the first to get cut.

In large homes occupied by small families, where family members have their own bathrooms, separate living rooms, playrooms, and other areas, points of natural social connection have largely disappeared. There are fewer reasons or opportunities to negotiate and interact.

The ACEs and faces of trauma

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are events in a child’s life or aspects of the environment that can undermine a young person’s sense of safety, stability, and bonding. These could include physical or emotional abuse or neglect in the home, a family member’s substance abuse or mental health issues, bullying at school, loss of family income, absence of a parent because of death, divorce, or incarceration, and more.

Kim Bressem and fellow Granby school psychologist Heidi MacDonald conduct professional development on trauma-informed classrooms at CEA’s Early Career Educator Conference and other forums for teachers.

“These all have impacts on children, and they’re felt all the way through adulthood,” Bressem says. “It’s not just genetics that plays a role in diseases we get as adults, but ACEs.” In fact, studies have shown a 20-year decrease in life expectancy for individuals who have five or more ACEs compared to those with none.

So, how do ACEs manifest themselves in children?

Much depends on what’s going on with the child, with stress responses ranging from fight to flight to freeze. Children could be yelling, hitting, or throwing. They could be procrastinating, fidgeting, or running away. They could be hiding, zoning out, or not completing their work.

In schools, says MacDonald, ACEs could look like absenteeism, expulsion, retention (staying back), dropping out, poor performance, or lack of preschool readiness. When there is trauma or fear, the amygdala—our brain’s emotional command center, which governs our feelings—takes over, and the thinking and analysis parts of the brain shut down. In students, therefore, trauma can result in reduced ability to learn, remember, respond, figure things out, make friends, or manage relationships. It could lead to fighting, defiance, or simply ‘checking out.’

In short, students who experience trauma can be underreactive or overreactive to stress.

“Among our littlest learners, depression doesn’t often look like lethargy or withdrawal,” MacDonald points out. “It looks like agitation and acting out. Children might be disruptive or aggressive. They might self-harm. Trauma expert Dr. Micere Keels described it best when she said, ‘Behavior is the language of trauma. Children will show you before they tell you that they are in distress.’”

For many students, trauma presents with physical symptoms such as chronic headaches or stomachaches.

“If you notice these patterns, it’s important to communicate with your school nurse and others with relevant expertise,” Bressem says. “Also, if you’re seeing stress-reactive behaviors in students, check to see if they’re outside their zone of proximal development. See if they need scaffolding or reduced complexity. Aggressive curriculum and overtesting are stressors too.”

Dos and don’ts

Behaviors, of course, can be problematic in school, which is why it’s important to not only understand underlying causes but also get students the help they need. No discussion of confronting childhood trauma and behaviors is complete without mentioning educators’ responsibility as DCF mandated reporters as well as their statutory rights in cases of student aggression or assault. (CEA provides free, in-depth training on both of these topics.)

“None of these kids wakes up wanting to give you a hard time,” says Bressem. “You don’t know whether someone is fighting a battle, so treat everyone as if they are. It can be frustrating, but remind yourself to give your students some grace. Troubled children and teens often decide, ‘I’m going to reject you before you have a chance to reject me.’”

“Take your most challenging students,” says MacDonald, “and work with them. One of the easiest, most effective SEL strategies is this: for two minutes a day, ten days in a row, have your most difficult student talk to you. Invest in that child. It can be awkward at first, but it works. Start with your hardest kid.”

Some interactions that are typically positive, it should be noted, can be triggering for children experiencing trauma at home. Asking students to recall what they did over the weekend or summer or describe what they have planned over a holiday break, for example, can be fraught with problems, Bressem and MacDonald caution.

“Those times are the worst for some kids,” MacDonald says. “Maybe you’re the most reliable adult in their life; maybe you’re their person, and being away from you for days or weeks on end is devastating.”

In fact, she says, behaviors often spike just ahead of school breaks.

She also cautions, “Tell students when you’re going to be absent. Let them in on the secret, because it’s a big deal to go somewhere and not have your person there.”

Poverty is another ACE, and many children who lack school and home essentials try hiding that reality from their teachers or peers. A student might say, for example, that she left her sneakers or backpack at a relative’s house. You may find a way of “discovering” an extra such item at home and giving it to that child.

“I was a latchkey kid at eight,” says MacDonald. “I grew up poor. Think of the teacher you needed at the age your students are, and try to be that teacher. You don’t have to go out and spend money, but you can be creative, and you can be an ally.”

Laying the foundation

Fortunately, not all children develop significant challenges after experiencing a traumatic incident or even several traumatic events. “Often that’s because they have the supports they need to withstand those traumas,” explains Dr. Maureen Ruby, endowed chair of social, emotional, and academic leadership at Sacred Heart University. Ruby, who began her career as an elementary and middle school teacher and reading consultant, presented this summer at a daylong conference, Recentering Joy and Empathy in the Classroom, that was a collaboration between CEA and SHU’s Teacher Leader Fellowship Academy.

“Some children’s lives are significantly altered by traumatic experiences,” says Ruby. “Those with complex trauma view the world as threatening—a place where they are not valued, and others can’t be trusted. That can have obvious negative impacts on their behavior and academics, because their focus is on survival. Teachers need to know this about their students: their brains have built-in alarm systems that detect potential threats and help their bodies respond quickly and efficiently to maintain safety. For educators, who are charged with supporting students’ academic and social emotional development and success in the classroom, trauma poses significant challenges.”

“Some children’s lives are significantly altered by traumatic experiences,” says Ruby. “Those with complex trauma view the world as threatening—a place where they are not valued, and others can’t be trusted. That can have obvious negative impacts on their behavior and academics, because their focus is on survival. Teachers need to know this about their students: their brains have built-in alarm systems that detect potential threats and help their bodies respond quickly and efficiently to maintain safety. For educators, who are charged with supporting students’ academic and social emotional development and success in the classroom, trauma poses significant challenges.”

Our brain’s neocortex, Ruby explains, helps distinguish between real threats and potential threats or nonthreats. But the neocortex is not fully developed until we are 25 or older, so it can be like a smoke detector going off in the kitchen. Is it because there’s an actual fire in the home? Or do we just have an overdone pancake?

Ruby had workshop participants play a game to demonstrate how brain architecture can be weakened by toxic stress but also strengthened by positive supports and experiences.

Working in small groups, participants’ goal was to build as tall a “brain” as possible—using pipe cleaners—and make it as strong and resilient as they could. With a roll of the dice, they built a base for their brain structure using the number of social supports they rolled. At each turn, they might draw cards representing positive life experiences (which allowed them to add straws to support the brain structure) or “toxic stress” cards that called for adding structure without supports. Weights were later added to represent additional life stressors.

“We saw the powerful role relationships play in early brain development,” said one educator, a high school teacher with 120 students per year. “What happens in those early years is critical. We can look at a high school student in the moment, today, but knowing where they came from and what they experienced helps us really understand them. It’s also clear that we need to do better by our children before they get to high school.”

“Our group had so many adverse experiences in this game that we had to stop charging forward and building taller,” said Stratford fourth grade teacher Kathleen Lozinak. “We had to focus on reinforcing and strengthening what we had.”

Weston art teacher and tier-two interventionist Carla Volpe added, “As we were building our base, the aspiring educator in our group reminded us that we needed to keep reinforcing. The base needed to be strong.”

“Every year is hard, and every year is important, but those early years can make it or break it,” said Ruby. “Kindergarten needs to be joyful, playful, and developmentally appropriate. Sometimes people think of teaching kindergarten as ‘cute,’ but it’s so much more.”

It starts with you

In demonstrating the importance of early supports, the brain game “reminded us to set the stage at the beginning of the school year too,” said one TLFA participant.

“Regulated classrooms start with regulated teachers,” says Bressem. “You take care of a lot of people, and you need a plan for yourself. Career-sustaining behaviors include taking your breaks, focusing on what you did well, and working in teams. Try this: Make two columns. One is all your personal supports—the people you trust, that someone who is always there for you. The other includes your community supports: crisis lines such as texting HOME to 741741, suicide prevention lifelines, national disaster relief lines, employee assistance programs, and more. Keep those handy. That’s your mental health PPE.”

- For more on trauma-informed teaching, including workshops on combating student isolation and cultivating community in the classroom, click here.