Bridgeport teachers are hardworking and dedicated but face a myriad of challenges including severe staff shortages, a lack of resources, and insufficient support. During a recent visit to three Bridgeport schools, NEA, CEA, and Bridgeport Education Association leaders were able to see what’s happening in schools and hear from teachers first hand.

NEA Executive Committee member Hanna Vaandering joined BEA President Ana Batista, CEA Vice President Joslyn DeLancey, CEA Secretary Stephanie Wanzer, CEA’s NEA Directors Tara Flaherty and Katy Gale, and CEA UniServ Rep Eric Marshall for a tour of three Bridgeport schools Friday ahead of a BEA Black History Event recognizing long-serving African American educators.

The group first toured the Bridgeport Regional Aquaculture School, which offers Bridgeport students and those from surrounding communities the opportunity to learn subjects such as boat building, marine engineering, and aquaculture. They watched a group of students reverse engineering a paddleboard in one lab, while in another area they saw students inspect seaweed for the presence of diatom algae. Students grow seaweed and raise koi at the school, which are then sold to area restaurants and businesses respectively.

Following the school visits, CEA Vice President Joslyn DeLancey, CEA Secretary Stephanie Wanzer, NEA Director Tara Flaherty, NEA Executive Committee Member Hanna Vaandering, CEA President Kate Dias, NEA Director Katy Gale, BEA President Ana Batista, and CEA UniServ Rep Eric Marshall stopped by the BEA offices.

Dozens of different languages are spoken in Bridgeport schools, and over the last several years, the number of English learners has increased by more than 500 each year, now approaching 5,000 students—almost a quarter of the full student population.

The union group visited a new arrivals center the district has opened at Central High School to provide students and their families with one-on-one assistance with registration as well as a language assessment. A class at the school is tailored especially for students ages 13 through 18 who had their education in their native language interrupted.

Cesar Batalla is a K-8 school, and the largest bilingual elementary school in Connecticut. Spanish-speaking students can grow their skills in their native language while also learning English.

In one classroom, the group was introduced to 29 students—many of whom are recent arrivals from all over Latin America. With so many students with varying levels of English language skills, the teacher explained that it’s hard to meet their differing needs.

Teachers at Cesar Batalla shared with Vaanderling and the CEA leaders the many challenges they faced prior to the pandemic that have now worsened.

“It’s disheartening and disappointing that the federal money our district received has not trickled down to the students,” one teacher said.

One of the school’s custodians retired in the fall and has not been replaced.

“I’m on my hands and knees scrubbing the floor on Monday mornings,” a teacher said, while another chimed in that she’s had to bring in a mop and vacuum from home.

The school has a severe shortage of all personnel, including teachers, and when a teacher is absent, students from one class are divided up and moved temporarily into other classrooms with no regard for grade levels.

Even for long-term absences, there are no substitutes. Teachers said that 13- or 14-year-old children are placed in first, second, or third grade classrooms for weeks at a time. Educators worry that it’s not appropriate for the younger children and that the older children are missing out on their education.

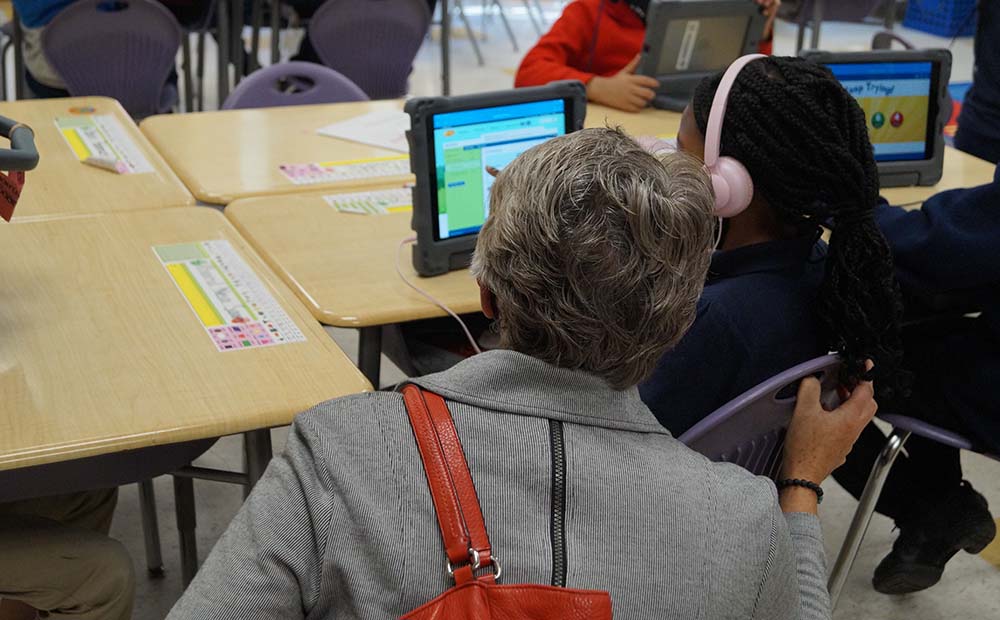

A Cesar Batalla student shows Vaandering what she’s learning in class.

“Staff are leaving in droves, I’ve never seen anything like it,” one teacher said.

Another added, “We are exhausted. I have my sixth-year certificate, I’ve been teaching 15 years, and I need a second job to make ends meet. We have to use Donors Choose and rely on our family and friends to fund the things we need for our classrooms.”

“Social emotional learning is rightly our priority for our students, but there’s no SEL for us,” another teacher said. “I’ve had to ask another teacher to cover my class so I can go in the bathroom to wash tears from my face.”

The teachers also said that a stronger stand is needed against standardized testing, estimating that nearly one third of the school year is lost to assessing students.

“Our new arrivals who speak no English are forced to take the PSATs with no accommodations except for extra time,” a teacher said. “What it does to our students is disgusting.”

Another added, “The kids are not well, and we’re not helping them with what they need by asking them to sit and be quiet and take tests.”

“What you’re doing for these students is amazing, and your love for them is palpable,” said Vaandering. “We have to stop this crazy focus on testing and what it’s doing to our students.”

She urged, “We need you to tell your stories in order to change lawmakers’ minds. Please speak up and help us change policies to make schools better for our children.”

“We have an extreme teacher shortage, and it has nothing to do with the children,” a teacher said. “Pre-COVID I’ve had desks thrown at me, been spit on, bit—I have the nicest class ever this year. It’s not the children, it’s the policies. The people in authority have no idea what’s going on in our classrooms.”

Click here to share your story about what’s going on in our schools that policymakers don’t see.