“Music has a tremendous impact on kids and their ability to learn,” Al deCant, who has served as an elementary school teacher, principal, and director of curriculum and instruction in districts across Connecticut, told educators gathered for the first Artists and Educators Children’s Songs Conference and Festival.

Citing music’s effectiveness in aiding with memorization and enhancing children’s cognitive abilities he added, “Ninety percent of a child’s brain becomes active when they participate in music.”

The Conference and Festival held at Mitchell College was hosted by the Aspiring Educators Club and Department of Education and co-sponsored by the Alewife Cove Conservancy and CEA.

The conference portion featured two hands-on breakout sessions: one for artists looking to learn more about writing and producing children’s songs, and another for educators to explore the use of music in the classroom. The session for artists, led by children’s musicians Steve Elci and Greg Lato, focused on the business of making children’s music and contemporary recording and mixing techniques.

DeCant, known as “the Singing Principal,” opened the session for educators, which focused on the incorporation of music into early-childhood and elementary classrooms. Music has been central to deCant’s career as an educator and educational performing artist, and he currently performs in schools, libraries, and other venues throughout New England.

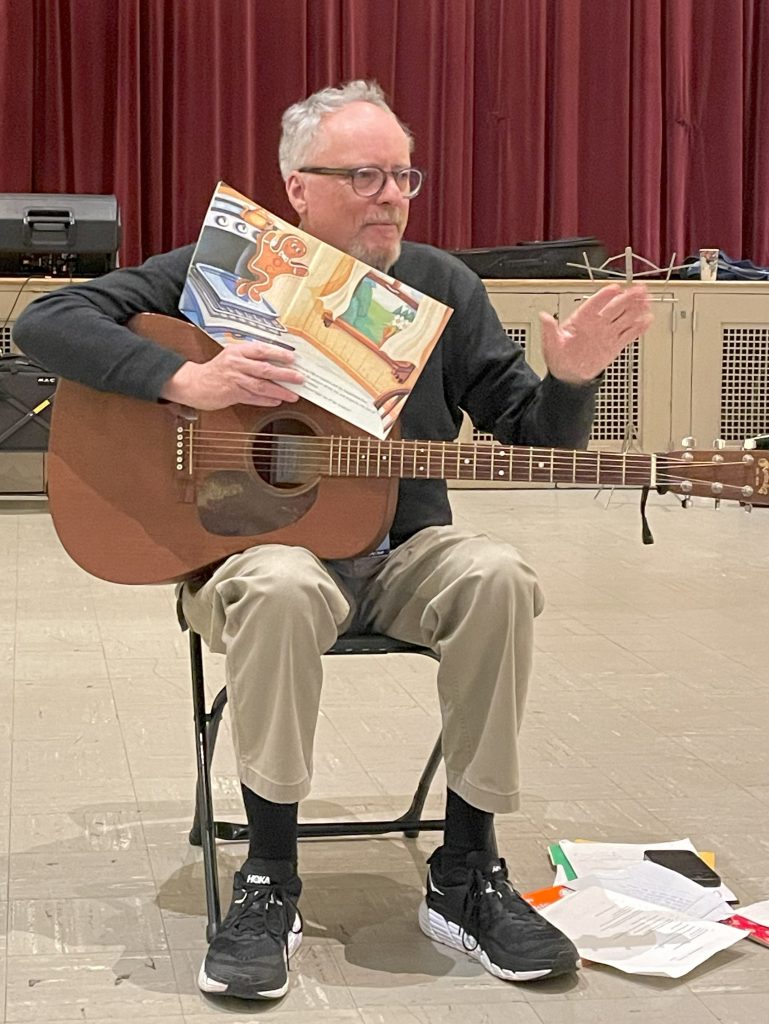

Al deCant modeled songs and strategies he uses with young learners.

In his workshop, deCant modeled songs and strategies he uses with young learners, having participants sit in a circle and participate as if they were young students. He brought out his guitar, books, and various props to demonstrate various modes of integrating music into classroom routines and learning objectives. As he did so, he explained the pedagogical value of each exercise.

For young children especially, deCant said, songs used in the classroom should incorporate five elements: call and response, repetition, prediction, organized movement, and controlled dynamics of tempo, emotion, pitch, and volume. According to deCant, not only do interactive musical exercises help teach children how to match pitch and have good rhythm, but “children retain fifty percent more information when movement is involved.”

DeCant emphasized that music is especially useful in the teaching of reading. “Children that have a good sense of rhythm at an early age become better readers at an early age.” Moreover, like songs, books for early readers have rhyme and repetition to reinforce reading skills and build phonemic awareness.

The session’s second presenter, Chris Clouet, also focused on how songs can support reading instruction. Clouet is the chair of Mitchell College’s education department, and a former teacher, principal, and superintendent. In his workshop, he brought out his guitar and copies of some beloved children’s books.

In a model lesson on Ferdinand the Bull, Clouet, who speaks Portuguese and Spanish, demonstrated how, in addition to reinforcing the language of the book through song, the presence of the guitar invites students to make interdisciplinary connections. Spanish-speaking students will be able share their multilingual understanding of words like “matador” and “guitar,” which can open discussions about the Spanish origins of the guitar as an instrument. The guitar can also help students build numeracy when teachers ask questions like, “By listening, how many strings are on the guitar?”

Chris Clouet, chair of Mitchell College’s education department, focused on how songs can support reading instruction.

Teachers who cannot play the guitar need not fear. Clouet, “a big believer in mixing digital music resources” with more traditional forms of music-making, read Green Eggs and Ham to a digital rhythm track to demonstrate the connections between rhythm, rhyme, and reading.

For workshop attendees, the event was engaging and energizing. Elainy Regalado, an assistant teacher at the TVCCA preschool in New London, said that while she already makes frequent use of songs in her classroom, she wants to begin using some of the songs and movement strategies taught at the workshop. She added that the workshop made her “realize the importance of the connection between song and cognitive development,” and inspired her to try to create new songs herself.

At the end of the conference portion, the presenters encouraged teachers to find the bravery to get silly and be creative with music in their classrooms. “If you’re a teacher, even if you’re not a musician, you’re on stage — teaching is a stage. The music comes later,” said Steve Elci. “Every day you do a little more, try something different…At some point it just clicks.”

The conference was followed by a Children’s Songs Festival during which the presenters performed a concert of their songs for local children and their families. Chris Clouet was joined in his performance by one of Mitchell’s first-year early childhood education students, Preston Cheng. While Cheng says that he has only recently started “getting into music” and playing the guitar, he loves performing songs and interacting with kids. He says that the conference and festival will leave an impact: “I gained a lot of experience and information that I will transfer to my future classes.”

The presenters hope that this will become an annual event and continue to grow in attendance. Citing Walt Whitman, Clouet said, “People contain multitudes. Teachers can be more than one thing. Teachers can be artists too.”