Pandemic learning has tried educators and students as never before, but teachers are finding this year has also taught them lessons they’ll use going forward.

“We’ve been given significant insight into what kids really need—particularly the needs outside normal academic expectations,” said New Britain Federation of Teachers President Sal Escobales.

Escobales joined 2020 Connecticut Teacher of the Year Meghan Hatch-Geary, Interim Dean of the Neag School of Education at UConn Dr. Jason Irizarry, and Dean of the Quinnipiac School of Education Dr. Anne Dichele during a panel discussion at last week’s Educator’s Rising state conference.

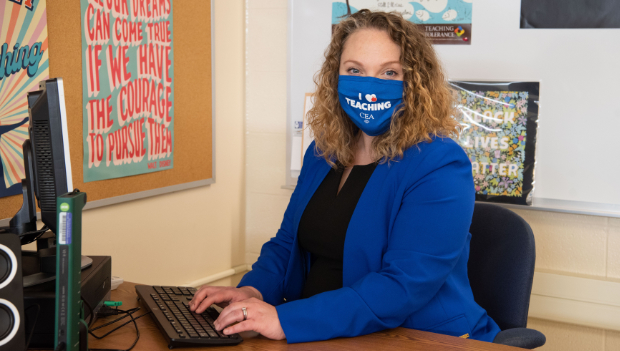

“The issues most evident to teachers during the pandemic have existed long before COVID,” said Hatch-Geary, an English teacher at Region 16’s Woodland Regional High School. “There are so many lessons to be learned. It’s been an awful situation, but it’s also been an opportunity for growth. As a teacher I’ve learned many new skills.”

Hatch-Geary said that what teachers really need at this point is time to reflect and collaborate—to talk about what they’ve learned as far as best practices and ways to individualize instruction.

“I’ve discovered that a lot of my students love paper,” she said. “Going forward I’ll make sure we make things available in both analog and digital formats.”

Escobales agreed, “We need to find a healthy balance between paper and technology that matches individual students’ needs.”

Hatch-Geary also said that during the pandemic she has let go of focusing on grades in the way she would during a normal school year.

“It’s been a huge paradigm shift. I’m focusing on feedback and giving students less stuff to manage to really allow for individualized feedback in a timely way. And I’m allowing students to revise that work, too. Sometimes we get very caught up in pacing and gradebooks, and those aren’t necessarily the things that are going to help our students the most,” she said.

Dichele said that education is often structured to manage the failing student. “How do we look at what really produces learning? Mistakes are not failure.”

Escobales wondered what education will look like post pandemic. “Our definition of mastery and communicating it to children needs to be beyond the letters of the alphabet.”

Though he himself is a high school teacher, as president of his local Escobales said he’s had the opportunity to spend time in elementary schools. He said he expects some of the young children who have spent this year as remote learners to have trouble reacclimating to the many transitions of the school day and the rhythm of a classroom.

Balancing the academic and social sides of school may also be hard for some students, he said.

“Many of our students are looking forward to enjoying time with friends when they come back to school, and they’ll have to have the mental fortitude to be open to instruction. How do we help let them know it’s okay to socialize, but we also need to get back to academics?”

Escobales lamented what students in their last year in a school building—such as those in 5th, 6th or 8th grades—missed out on with not being in their physical school building during a transition year.

“All of these things are going to come crashing together when we get back to normal school,” he said. “It’s not going to be a one-year transition. Kids are not going to snap back within a year.”

Hatch-Geary said that another lesson from this year has been the value of partnering more closely with families.

“Building caregivers into the learning process has been extremely beneficial to everyone involved,” she said. “I’m looking forward to opportunities to do things differently going forward.”