Sometimes opportunities disguise themselves as obstacles, said one of the nearly 70 participants in a virtual training for teacher leaders. The topic was equity in education, and the question was how to achieve it.

“In June, we held the Road to Equity forum with over 200 members, and today is the next step in our journey,” said Stamford teacher Sandra Peterkin, ethnic minority director at-large for CEA’s Ethnic Minority Affairs Commission (EMAC).

“We need to hold districts’ feet to the fire so that there is an equal opportunity for every student to hit a homerun in education,” said EMAC Chair Sean Mosley, who teaches in Waterbury.

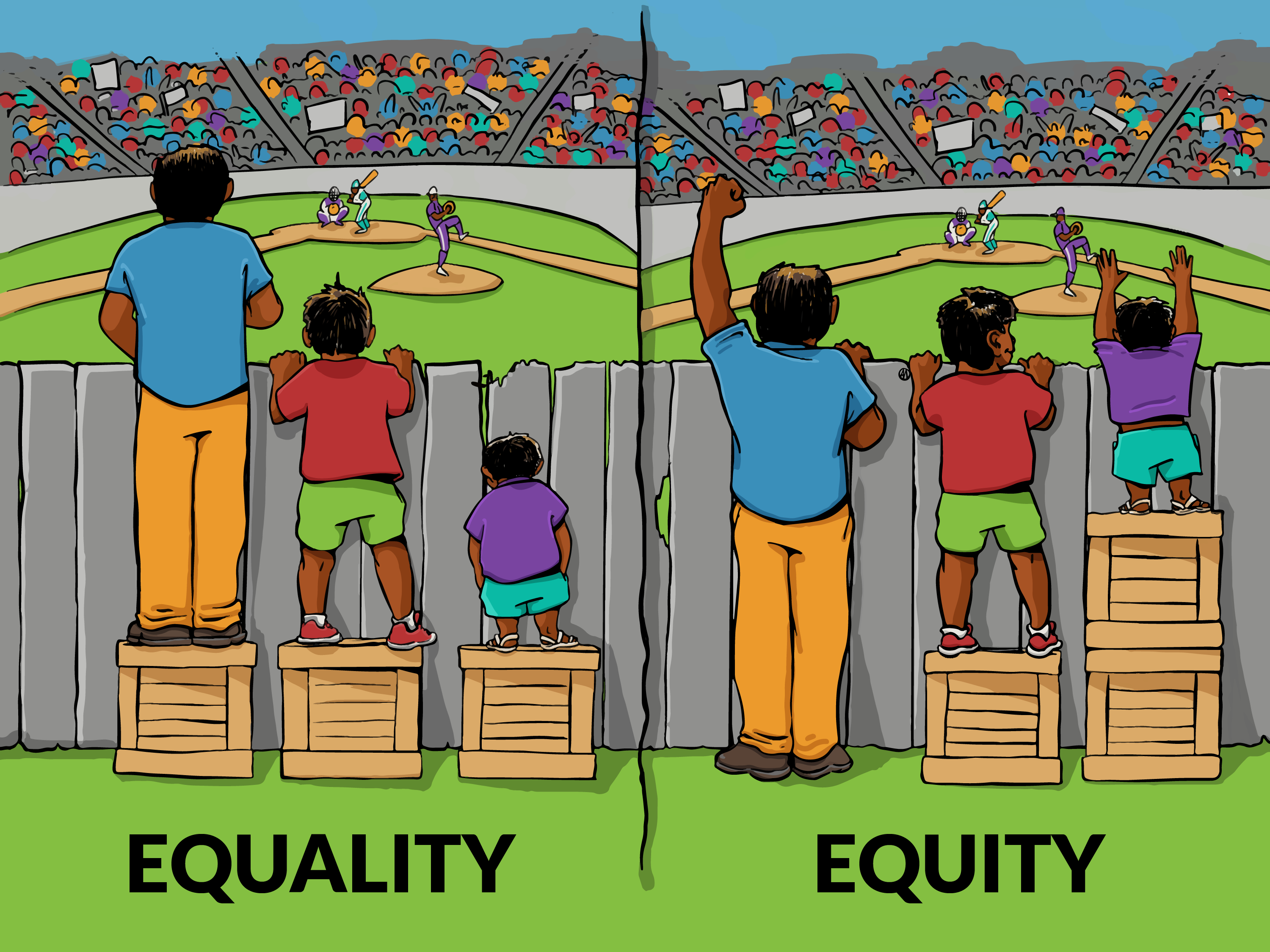

That, said Westport educator Faith Sweeney, means making sure all students are seen, valued, and heard. “While we fight for equality, we need equity to make all our children are whole and all our schools are whole,” she observed.

Step one, said CEA regional organizer-trainers Herman Whitter and Mike Breen, is to gather data. They presented participants with a school equity assessment, a checklist that asks dozens of specific questions to help teachers examine how intentional their districts are at addressing equity issues. Questions include

- Does your school’s faculty represent the diversity of the state?

- Does your school offer technology support, such as a help desk for families?

- Are accommodations made for staff or students who do not have instructional or safety materials?

Gathering data as well as anecdotal information, said CEA Government Relations Director Ray Rossomando, assists local associations in organizing around equity and helps inform state legislative actions to ensure students receive an equitable education.

Long-standing educational inequities, such as lack of access to technology and resources, were exposed and exacerbated by the current global pandemic, said CEA Vice President Tom Nicholas, a school social worker who oversees an NEA grant to address diversity in Connecticut’s teaching profession—another area where gaps exist.

Next steps

“We get the data—now what? What do we do with it?” asked CEA Training and Organizational Specialist Joe Zawawi. “We organize around it.”

Zawawi emphasized the importance of relationships within schools and in the broader community to get things done.

“That means you go person by person and identify who will help you, who are the activists and natural leaders—people who do the work of the union, who are trusted and respected and buy into the work you’re doing. They bring others along with them.”

“Relationships are key,” Whitter agreed. “Approach people you know. Ask them to join with you. Many people don’t get involved simply because they’ve never been asked. Also look at who might already be involved in social justice inside and outside of school. Bring them in.”

“Organizing is about building power,” said Zawawi, “and you can’t build power without people. You don’t survey or send emails; you have conversations to see where your fellow teachers stand on the issues. What do you know personally about them? How are they connected to the community where you teach? You may not know all of your colleagues, so enlist help from teachers you know to identify teachers they know.”

In order to build an effective, escalating plan, Zawawi added, it’s important to understand who has the power to make change at the building level, the district level, and the community level—as well as who might oppose your efforts. “That way, you can get out ahead of them and develop a plan to effect the change you want to create.”

A plan for achieving equity in education could start with something easy—such as presenting data from your local school equity assessment to your principal or superintendent. If your calls for change are met with resistance, you might circulate a petition and present it to your board of education.

“If the board decides not to act,” said Zawawi, “keep escalating until you have a satisfactory resolution to your issue.”

Rossomando also noted that data collected in equity assessments, as well as teachers’ personal anecdotes, can be powerful tools for pushing state-level policy change. “Teachers should share their stories with legislators and make those personal connections. The energy and observations made at the local level can have a great impact statewide.”