Districts around Connecticut are preparing to send their reopening plans to the State Department of Education by tomorrow’s deadline, but how those plans have been developed and the provisions they contain vary widely by district.

Despite Commissioner of Education Miguel Cardona’s repeated urging that districts collaborate with educators and local unions, in some districts, teachers’ voices have not been included and their concerns have not been addressed.

CEA’s Safe Learning Plan calls for local school reopening committees to include teachers from the elementary, middle, and high school levels, parent representatives, a school health representative, and the presidents of local bargaining organizations; however, some districts have not met even this easily achieved requirement.

Local association leaders have been working day and night to advocate for their members during this time of uncertainty as the stakes are higher than ever before. Here, three local association leaders share how their districts, Danbury, Stratford, and Marlborough, have been preparing for school reopening.

Danbury

NEA Danbury President Erin Daly was one of the few members and only union leader representing her thousand-teacher association on her district’s reopening committee and has requested her name be removed from the district’s draft plan.

“While the district hosted several listening sessions, the committee never answered the questions I conveyed on behalf of members,” says Daly. “We never actually worked on the plan during committee meetings—that was all done offline with only a select group.”

Daly says that the Danbury plan mimics the state plan and does not provide the specifics parents and teachers need in order to be confident about a safe reopening.

“When the district said it was going to release the draft plan to teachers and parents last Thursday, I was absolutely aghast. I’m supposed to be representing a thousand members and many of our questions have not been answered,” she says.

Daly has been receiving emails from more than 100 members every day and is frustrated that she doesn’t have answers for 90 percent of them.

Danbury teachers who are immunocompromised are concerned, Daly says, as they have not yet been provided with tangible options for accommodations.

“This is weighing heavily on teachers’ minds,” she says.

Daly is working with her UniServ Rep to get clarification about accommodations for members but is very disappointed the district did not provide any assurances for teacher safety in its reopening plan. “They’re telling us, ‘Put on a mask, show up, and hope for the best.'”

Rapidly increasing enrollment in Danbury had already put schools in a tough position prior to the pandemic, and it now presents a significant health hazard as the state calls for full in-person learning. Most Danbury families have indicated their children will return to in-person learning if that option is available.

Because the large number of students attending Danbury schools would preclude social distancing measures, Danbury is petitioning the state to allow the district to start the school year with a hybrid model. Under the proposed hybrid model half of students would attend school Mondays and Tuesdays and learn remotely Wednesday through Friday while the other half would learn remotely Monday through Wednesday and attend school on Thursdays and Fridays. English learners and special education students could attend in-person school up to four days a week.

“I am on board with the hybrid plan,” Daly says. ” I support our Superintendent’s efforts to create a plan that works for Danbury. With our overcrowding it’s not doable or safe to go back in Danbury with in-person learning for all students every day.”

CEA’s Safe Learning Plan calls for beginning the year with remote learning where necessary and to allow for staggered schedules to reduce density, as Danbury would like to do.

“I’m 100 percent in agreement with everything in the CEA plan, and it’s one our members would support,” says Daly. “If we follow the state guidelines I don’t think there’s enough money for us to go back safely to full, in-person learning.”

In a letter to Governor Lamont, Daly wrote, “For a district such as Danbury that continuously ranks dead last in the state for per pupil spending, the state plan relegates our students and staff to be nothing more than sacrificial lambs in our return to school.”

Stratford

There was no official Stratford Education Association representation on the district’s reopening committee, and the superintendent did not share the reopening plan with SEA leaders until she sent it to the state this afternoon.

“We worked with our UniServ Rep to submit our first draft of an MOU, and one of the points we made was that we wanted the right to review and make suggestions to the plan before it was submitted to the SDE, but we didn’t get to see the plan until it was already finalized and sent,” says SEA Secondary Vice President Kristen Record.

The district sent a survey to all employees this week asking how likely staff members are to request a leave of absence, but there was no mention of remote work or in-building accommodations—a significant concern to teachers. Many who are at higher risk if infected with the coronavirus and are seeking accommodations want to know how it will be decided who receives remote teaching assignments if more teachers request that accommodation than there are assignments.

Record says that another big concerns for teachers is with the “when/if feasible” language that is included a dozen times in the state plan.

“When the state’s plan was first released some people didn’t realize so much of it is so loose,” says Record. “Some people thought those items, like the six feet between student workstations, were requirements, but they’re just suggestions. All of a sudden that’s being more widely understood by parents and others in our community.”

Record, who teaches high school physics, estimates she could fit approximately 16 desks in her classroom with four feet between each. High school classes generally range from 20 to 30 students. An initial survey of Stratford families indicates that 26 percent are planning to take part in remote learning.

Most of the provisions the Stratford superintendent has told SEA leaders are contained in the district’s reopening plan relate to the elementary and middle school levels, but few items cover high schools. At the middle schools, students will not be using lockers, and will instead be permitted to carry backpacks from class to class, which they are not typically allowed to do. Elementary and middle school students will eat lunch in their classrooms, but no information has been shared as to who will cover classrooms during lunch periods. Students will be allowed to carry water bottles, and water fountain use will be prohibited. Floor markings in hallways are planned to help facilitate social distancing.

Record says that teachers have asked about portable AC units, as most Stratford schools do not have air conditioning. At the elementary level teachers also have concerns about windows that open but lack screens. SEA leaders are asking the district to adopt a shortened day schedule for days with high temperatures in September.

The SEA has received no information about any updates underway or planned to district facilities.

Record says the CEA plan is a commonsense approach to reopening schools that sounds like it was written by people who work in public schools and understand what is actually necessary and feasible.

“Connecticut has done a good job of reopening while keeping the virus at bay because the state has opened slowly and methodically,” Record says. “I don’t see that happening with schools, and that’s causing a lot of anxiety for many people.”

She adds, “For the first time ever I’ve heard teachers talking about writing their wills.”

Marlborough

Marlborough is a single-school district that has experienced declining student enrollment in recent years and thus has space available to be converted into extra classrooms. Based on the results of an initial survey, administrators estimate 20 percent of families will take place in distance learning and 50 percent will drive children to school, allowing buses to operate at half capacity. The district plans to have bus monitors on every bus, at least at the beginning of the year, to ensure students are wearing their masks.

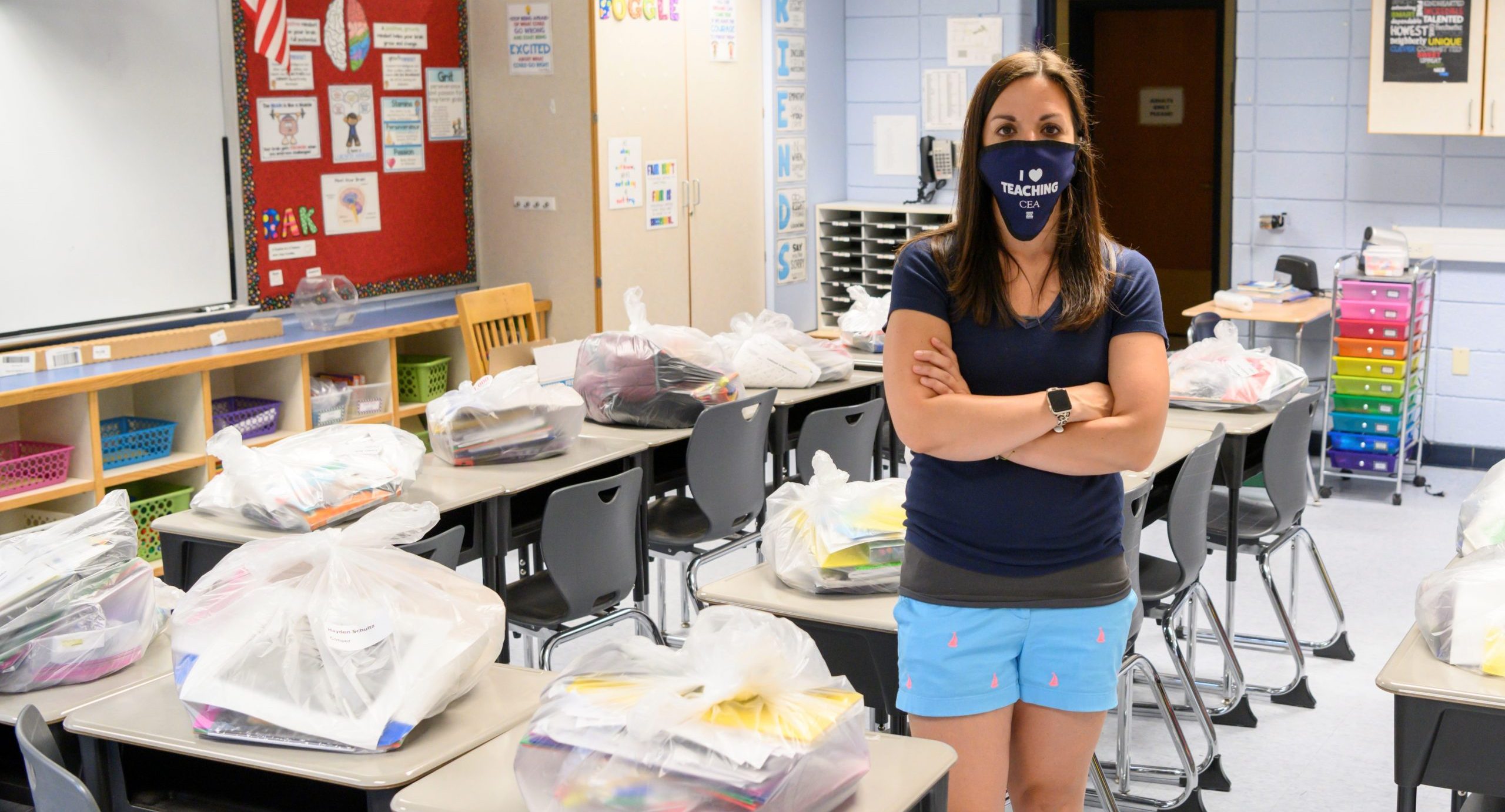

Many elementary teachers have had tables in their rooms, but to ensure more space between student workstations the district is pulling desks out of storage and purchasing 70 additional standing desks—equipment teachers have requested in the past and that will be used post-pandemic. Given the number of students likely to take part in remote learning, administrators estimate they will be able to keep classes at 14-16 students, allowing nearly six feet between desks in most rooms.

Given the smaller class sizes and other steps the district is taking, co-local president Amy Farrior says that a survey of members found teachers feel either comfortable or somewhat comfortable returning to in-person teaching.

Farrior, who teaches kindergarten, says it’s hard for her to envision how social distancing will work in the classroom for preschool, kindergarten, and first grade students. “I’m going to have to back down from my teaching philosophy. A social emotional curriculum is very hard to incorporate when students are sitting at desks, facing forward, and can’t collaborate.”

The cohorting model means Farrior’s students won’t be able to work with any students outside of her classroom as they normally do. “We won’t have our fifth grade book buddies this year, which is one of my favorite things we do in kindergarten. It’s some of those small things we’re going to miss the most.”

Farrior adds that young learners’ lack of self sufficiency is also weighing on educators’ minds. “They need help buttoning their pants after using the bathroom. No teacher I know is going to strong-arm a kid away from them when they need consoling.”

Farrior and co-local president Pam Farrington, along with the school psychologist and physical education teacher sit on the district’s reopening committee—which also includes parents, a paraeducator, the school nurse, and cafeteria staff, as well as town and health officials and school administrators.

The school is looking to eliminate as many touch points as possible by installing new touch-free faucets in the bathrooms, new paper towel dispensers, and exploring the purchase of hands-free soap dispensers. Water fountains are being switched over to water stations.

Farrior says that members are pleased with upgrades being made but are still wondering about many unknowns such as how fire and lock down drills will be conducted, how substitute teachers can be employed safely, and what will happen on hot days given that most classrooms don’t have air conditioning. Many teachers at the school have young children themselves, which could present a significant challenge if the schools or daycares educators’ children attend are forced to close or quarantine classes.

“I think everybody is anxious. Teachers are planners and control freaks and we don’t know what school will look like this year,” says Farrior. “Everything we know about school and how it works is being thrown out the window, and it’s going to be very different.”