What happens when an educator is given the rare gift of time and space to pursue their own learning? For East Lyme teacher Victoria Thomson, her year as an Albert Einstein Distinguished Educator Fellow with the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) not only deepened her expertise—it reenergized her. Stepping away from the daily demands of the classroom allowed her to reconnect with the passions that first drew her to teaching and focus on the power of science to tell compelling stories.

The Albert Einstein Distinguished Educator Fellowship (AEF) Program provides a unique paid opportunity for STEM educators k-12 to spend eleven months working in federal agencies or in U.S. Congressional offices. They apply their extensive knowledge and classroom experiences to national education program and/or education policy efforts while learning about federal agencies and engaging in a wide variety of professional learning opportunities.

Life-long learning

Thomson hadn’t heard of the AEF Program until her desire for in-depth professional learning led her to google paid teacher internships.

Victoria Thomson and Illinois teacher Sarah Compton, another Einstein Fellow who worked with the USGS, staffed a table at the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office’s Noche de Ciencias (Science Night).

“I’m a real life-long learner, and I wanted to be able to develop myself professionally in a way that I couldn’t through local opportunities,” says the high school science teacher. “I wanted to be able to have a sabbatical so I could read and do a deep dive into my subject matter. I don’t have space to do that ordinarily as a classroom teacher.”

The application process for the AEF Program is rigorous, including a trip to D.C. for semifinalists to meet with current fellows, and Thomson didn’t get accepted the first year she applied.

“It’s also important to show students they should try something even if it’s hard,” Thomson said. “Even if you know you might not get it, you should take a healthy risk.”

Thomson was accepted on her second attempt and says, while the AEF Program is an amazing opportunity for educators, it requires sacrifices not all teachers are able to make—including taking a full year away from teaching and relocating to Washington, D.C.

“We have a leave of absence in our teacher contract that guarantees I could return to my position after a year away,” Thomson says. Fellows come from all over the country, and Thomson says that teachers from states without collective bargaining had to quit their jobs in order to become Einstein Fellows.

Thomson is grateful her union had negotiated the possibility for a professional learning sabbatical into the contract, as well as for the backing of her superintendent who provided a letter to support for her application and recognized the value of the opportunity to both Thomson and the school community.

Data as a storyteller

Once the 15 Einstein Fellows for a particular year are selected, participating federal agencies choose which fellows they want to work with. Fellows don’t get to choose their agency.

Thomson poses at the Albert Einstein Memorial in Washington, D.C.

The 2024-2025 Einstein Fellows were placed with the Department of Energy, Library of Congress, U.S. Department of Defense, U.S. Geological Survey, U.S. Department of Homeland Security, and five were also placed in U.S. Congressional offices.

The fellows design their own PD plan for the year and receive funding to implement it.

“I focused on science communication and data as a storyteller,” Thomson says. “The USGS collects vast amounts of data—it’s not a regulatory agency. They collect data on things like water and elevation that towns use for planning. I spent time and money looking at how scientists and agencies communicate their information and how we can get that information into the classroom. Scientists’ expertise is as scientists, not as educators, so they’re not familiar with how to get their message into classrooms.”

She continues, “The USGS does a ground water monitoring program in my neighborhood in Niantic. I live in the same town where I teach, and I looked at ways the federal agency was doing research locally that I can use with my students.”

As part of the program, fellows take part in PD at different participating federal agencies and attend a variety of conferences.

“I loved going to conferences,” Thomson says. “I was able to meet three former NASA astronauts. I went to the NASA Goddard Space Center, and I also met a Nobel Prize Winner. I loved meeting so many interesting people and collecting lots of stories to tell my students.”

In another of Thomson’s endeavors as a fellow she worked with Montana State University, California State Polytechnic University, and the University of Notre Dame on a data science project with the Crow Tribe in Montana.

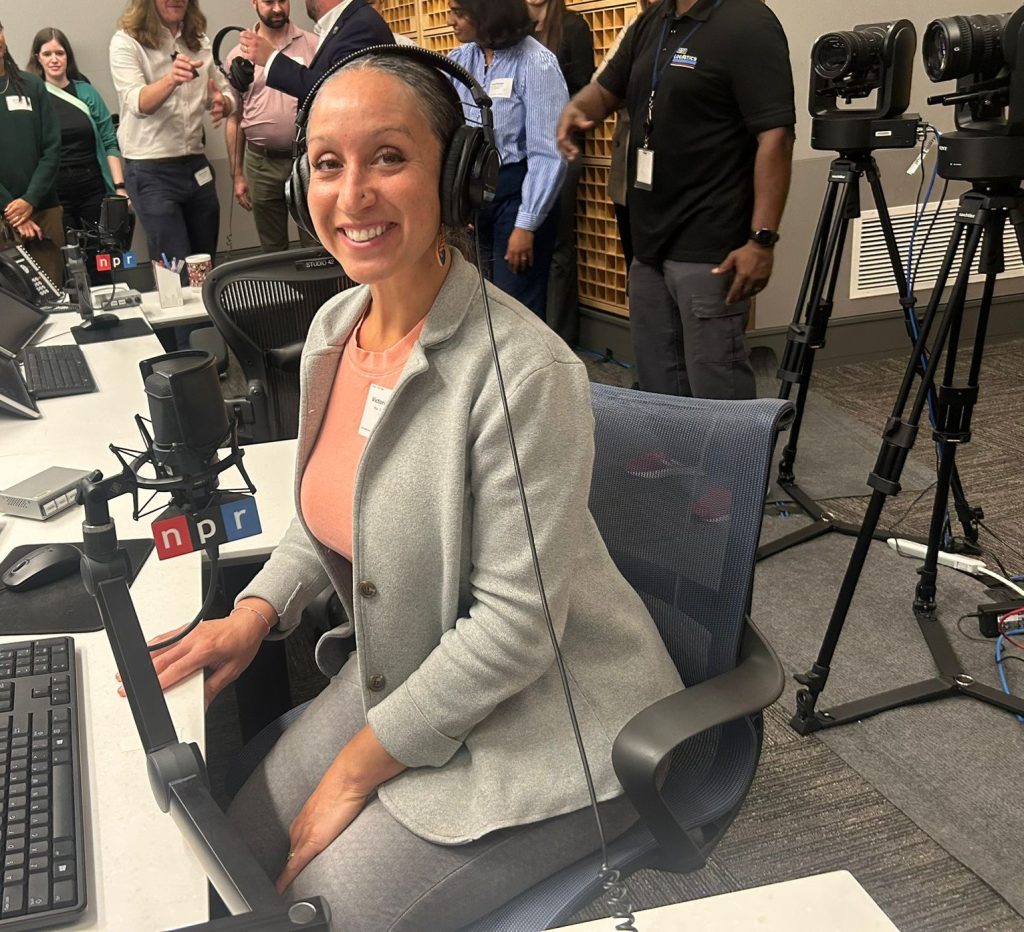

Thomson on a tour of NPR.

“I like the stories data tells, and I like making learning relevant,” Thomson says. “I went to high school in Montana, and it’s important for me to give back to Montana in some way.”

Staying connected back home

While working in D.C., Thomson came back to Connecticut most weekends to be with her husband and children, and she also maintained close connections with her school and district community.

“I was in touch with colleagues throughout the year,” she says. “I’d drop things off at school or come back and visit them.”

When she encountered interesting cloud classification information from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, she sent it off to a third-grade teacher she knows. She also developed an interactive game about amphibians that she piloted with the three elementary schools in East Lyme.

Thomson is now back in the classroom, collaborating closely with the two other teachers who instruct the same ninth-grade integrated science class. She plans to educate students about a ground water quality monitoring program happening in their community and if possible would like to get an educational stream gauge.

“The USGS has 10,000 stream gauges across the U.S. that measure water height and quality,” she says. “The entire nation is very dependent on these so we can prepare for flooding and rising water. It would be really cool if we could have an educational stream gauge that’s accessible for students.”

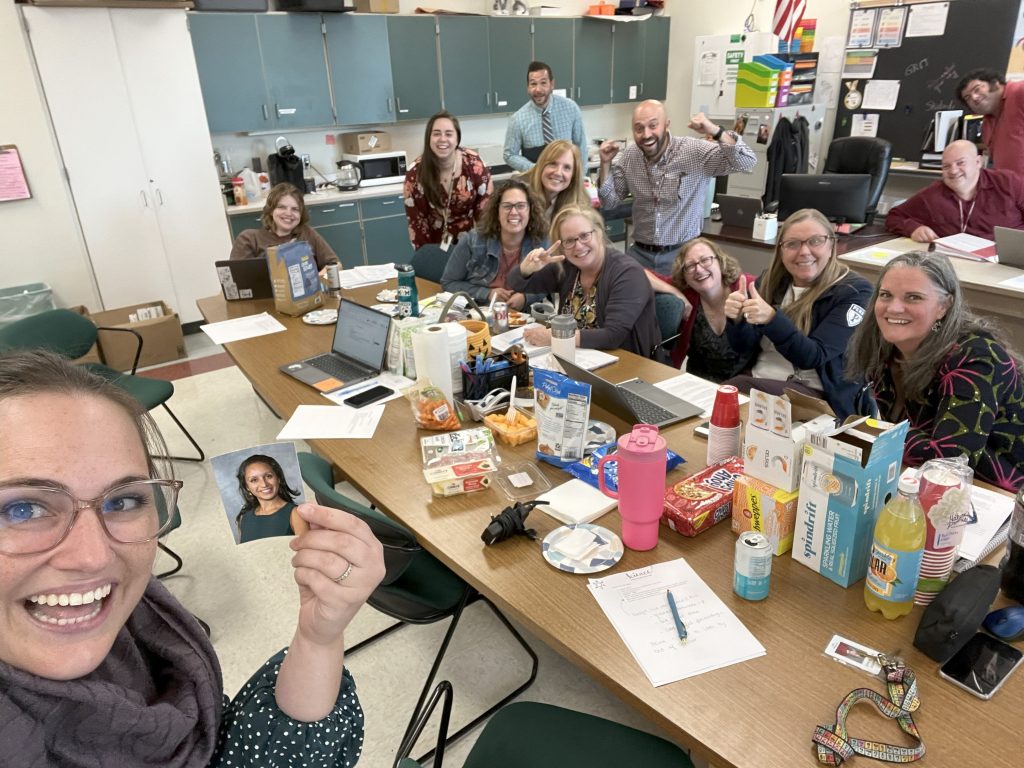

The East Lyme High School Science Department made sure Thomson had a presence at their meetings, even while she was in D.C.

She will also be advising a middle school club on biocoding concepts and wants to think holistically about how to provide additional science opportunities to kids k-12, not just for her own students.

“I heard over and over again from so many different people, ‘Talent is everywhere, opportunity is not.’ I want to shine a light on the opportunities that exist so more students are aware of them.”

At the Library of Congress Thomson met chemists who do research to discover what old paper is made of and what pigments were used in the past to ink books so that books can be best preserved from light. Thomson says so many unusual and fascinating careers exist in STEM, and she looks forward to talking to students about careers they’ve never heard of.

To bring her learning back to a wider audience, Thomson plans to speak to her board of education at an upcoming meeting to highlight some of her experiences and share what she’s bringing back from the fellowship experience to East Lyme students.

“I want our communities to know that they have trained, trusted professionals educating their youth,” she says.

Thomson says the fellowship experience enhanced her knowledge and also refreshed her enthusiasm for teaching.

“The energy we bring to our students is a direct reflection of our own energy,” she says.