Too many behavioral issues and curricular demands; too few resources and hours in the day. That’s the reality today’s educators face, and it’s the basis for a number of CEA-supported measures making their way through the legislature.

“We’re in this hugely reflective moment,” said CEA President Kate Dias, “where educators are thinking, ‘Why do I do this? Can I continue to do this? And am I willing to fight for it?’ We are hot into the legislative session, there are some significant pieces of legislation we are working to pass, and we have to keep our energy up. We came back from the pandemic to schools that looked the same and students who did not behave the same. How do we continue to care for them without sacrificing ourselves, because their needs have become so enormous?”

[Above, Deisha Quinones, Lauren Cook, Brandon Scacca, Mackenzie Brink, Nadia Wentzell, and Elise Capraro share their hurdles and hopes as new and aspiring educators.]

Speaking at CEA’s Early Career Educator Conference, Dias urged new and aspiring teachers to find their balance, their joy, their inspiration—and each other.

“The community we build as educators allows us to come back tomorrow,” she said.

The March 25 conference, which attracted 140 educators and offered a dozen professional development sessions, provided information on technology integration in schools, children’s literature, play-based learning, trauma-informed classrooms, educator self-care and time management, and more. A central focus was keeping early career educators—those in their first six years of teaching—from becoming overwhelmed.

Mindfulness over burnout

Teachers in their first five years are among the most likely to leave the profession, and those who work in special education, math, science, or a high-poverty district—in short, wherever there are chronic shortages—are at greater risk of leaving.

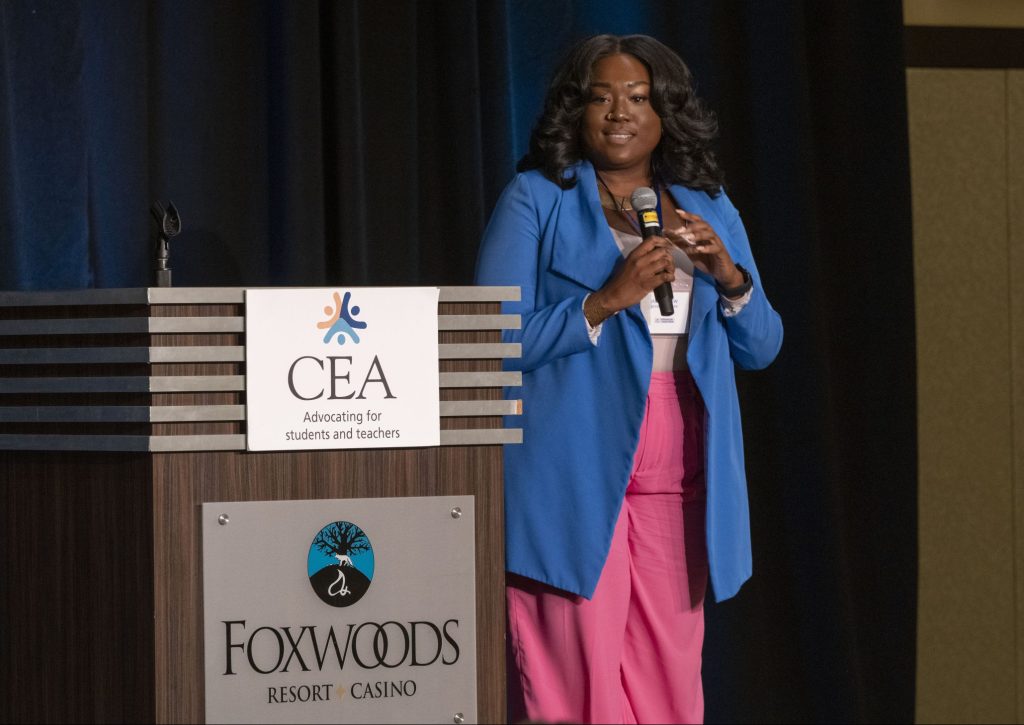

Keynote and TEDx speaker Jelan Agnew, a licensed clinical social worker, told attendees, “We’re giving at the expense of ourselves, because that’s what we have learned to do. Our burnout starts in our value system, and it lives in our nervous system.”

“One thing that grinds my gears is this ‘back to normal’ people have been talking about since the pandemic,” said keynote and TEDx speaker Jelan Agnew, a licensed clinical social worker.

“We need to talk about a new normal. We’re conditioned to multitask, so I was hustling and speaking with pride about how many different things I was doing and—long story long—I ended up in the ICU. My body shut down. My mental health shut down.”

When she asked who else was burned out, a majority of hands in the crowd went up.

When she questioned who’s getting enough rest at night, hands went down.

“Why do we feel like we must be ‘doing’ at all times?” she asked. “We’re giving at the expense of ourselves, because that’s what we have learned to do. Our burnout starts in our value system, and it lives in our nervous system. It’s important to invest in ourselves the way we invest in others.”

Agnew talked about mindfulness—doing one thing at a time and being present in the moment—as a way to overcome burnout.

“I know it’s a buzzword, and it’s simple, but it’s not easy. As educators, we know. But do we practice?”

Far beyond meditation or yoga, Agnew explained mindfulness this way: “Anything you can do where you lose yourself in the moment, that’s your mindfulness practice. Running, reading, baking, lifting weights, writing, singing, art, gardening, the hobbies you had as a kid—those are the mindfulness practices your soul chose for you. Ever watch a kid play? They’re mindfulness experts! Playing in the dirt, frolicking, they are fully present in the moment.”

She also described different ways of experiencing joy, including what she termed “little j” moments, where we notice the joy we’re already experiencing, and “big J” moments that we plan and look forward to with anticipation.

“We need experiences that are not just survival mode,” she said. “Educators especially need big J moments. That’s my clinical recommendation for you.”

Overscheduled

“Check yourself before you wreck yourself,” CEA board member and Aspiring Educators Committee member Katie Grant told participants in her workshop on time management and self-care. The third-year Manchester High School English teacher is herself a new teacher whose first year in the classroom took place during the pandemic.

Early career educators Mikala Smith and Katie Grant acknowledge the challenge of maintaining work-life balance in their first years and beyond.

“Who has the Sunday scaries?” she asked a group of early career and pre-service educators. “Who works weekends? Who’s at school an hour before contracted hours? Who stays late?”

Question after question, nearly all hands went up.

“We’re doing more with less,” said Stafford Education Association President Diane Glettenberg, a high school math teacher who came to education as a second career. “We’re all being asked to take on more responsibilities, and we can’t do any more with the resources we have.”

“I’m in overdrive every single day,” said Brandon Scacca, an aspiring educator at the University of Saint Joseph.

“I am always stressed,” added Nadia Wentzell, a student teacher in her final semester at USJ. “A trademark of this career is that you will go home and feel like you could have done more.”

“As a student teacher, I was running on coffee and adrenaline and feeling like everything had to be perfect,” Grant recalled. “But you can’t pour from an empty cup.”

“How do I leave at my contracted time and get it done?” asked New London elementary school teacher Mikala Smith, now in her fourth year. “I’m spending 52 hours a week on work. Where are the hours? Toxic positivity is this message of ‘Remember to take time for yourself’ but also ‘Report cards are due!’ When am I stopping? When am I standing still? I’m not.”

Veteran educators Christi Ingram and Diane Glettenberg wear #RedforEd at the Early Career Educator Conference, which is open to all CEA members. Glettenberg, who serves as president of the Stafford Education Association, said, “We’re all being asked to take on more responsibilities, and we can’t do any more with the resources we have.”

“The system is unsustainable,” Grant acknowledged. “We have a great opportunity to change that this year with legislation CEA is pushing for. But we also have to work from within. Let’s look at that never-ending to-do list. This profession asks everything and more of you, but just like students, teachers must Maslow before they can Bloom. We have to prioritize our self-care, set boundaries, and hold ourselves accountable—meaning when your calendar is getting full, make sure self-care isn’t the first thing you delete from it.”

Grant distributed a worksheet that asked participants to calculate the number of hours per week spent on activities ranging from sleep to work to recreation. Many were surprised by the findings and wondered where they could carve out more time for themselves without sacrificing in other areas.

“One of the questions on this worksheet was, ‘How do you manage your time?’” said Wentzell. “And my response was, ‘LOL.’”

First-year bilingual teacher Deisha Quinones, who teaches at a multicultural magnet school in New London, said, “I feel like I’m a perfectionist, which really messes with my time management, because things can pile up as I set high expectations for myself. I’ve always wanted to be a teacher, and now I see—this is what my mom warned me about! She’s been a teacher for 25 years.”

Fellow first-year teacher Elise Capraro, a mother of three, spoke of the challenges of finding a balance between work and parenting. “I teach fifth grade in Thompson, and I love it. But juggling everything can be hard.”

Streamlining tasks can help, said Grant. Planning and preparing meals for the entire work week saves time over a more scattershot approach. Setting a daily 10-minute timer for cleaning and organizing your space can prevent clutter from piling up. Saying ‘no’ to extra assignments can be key.

“You can also automate certain things, like placing a time limit on your apps or setting your phone to Do Not Disturb,” she added. “Self-care is sometimes subtracting certain things from your list, and it doesn’t have to be a huge undertaking—it’s whatever is feasible, reasonable, or manageable for your life.”